|

Click on the picture to see Aretha's full blogpost on her website: www.reeinspired.com

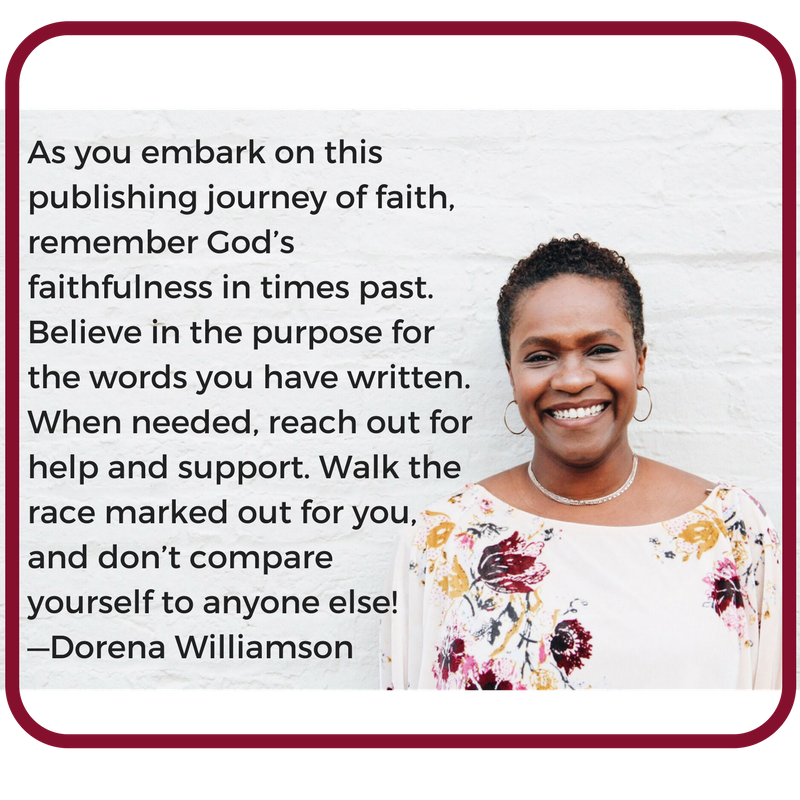

By Shannon Polk Associate Program Officer, Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, Flint, Michigan Printer Friendly Version (PDF) Originally Published For Assemblies of God Theological Seminary “The tyranny of hegemonic truth will have to be abandoned by those who treasure it and are privileged by it.” Alicia Vargas1 Everyone walks through the doors of the church with a cultural agenda believed to be normative. Often the basis of that framework begins with one’s assigned gender roles and, in America, expands to include class and race. For many people within the dominant group, other aspects of the paradigm will diminish, but that, unfortunately, is not the case for individuals without a dominant identity. Dual identity is the lens through which a woman of color sees the church. This duality structures her interactions within the ecclesiastical system, choosing neither gender nor race as the dominant framework. The duality of her presence in leadership can confuse people who may not fully accept her leadership in a cross-cultural context or who struggle with a non-male leader. Can the predominantly white Christian denominations receive the new wine that women of color in leadership have to offer? This is a variation of the question Superintendent Gilbert H. Caldwell asked of his ecclesiastical brethren around the issues of men of color leading in a predominantly white fellowship.2 Caldwell denied the myth that men of color ascend to senior levels within the administrative structure because the minority group has evolved enough to produce someone of sufficient caliber to function within that role. Instead, when men of color are elevated within the church, it is because the organization has evolved enough to allow someone outside of the hegemony to obtain a leadership seat. The hegemony commonly overlooks members of the minority group who are well-prepared for a leadership position. This is illustrated by the ascension of Beth Grant to the Executive Presbytery of the Assemblies of God (AG) and also illustrated by the election of President Barack Obama. Notwithstanding Grant’s exceptional credentials, the documented history of women within the AG Fellowship demonstrates that other women were equally qualified to lead as a member of the Executive Presbytery. President Obama’s election should not imply that he was the first man of color qualified to hold the office, but rather that it was not until the twenty-first century that the United States had evolved enough to be comfortable with a man of color at the helm. In these examples, predominantly white institutions embraced a new type of leader within the system—a Caucasian woman and an African-American man. However, strikingly absent is the person of dual identity ascending to significant senior leadership within these structures. Where are the women of color in leadership positions? Church Increase Due to Women and Minorities According to the statistics from the AG U.S. Minister’s Report, in 2008 no women served as district officials, and only eleven women served as district presbyters. Of the 6,502 credentialed women within the Fellowship, 1,316 were either retired or semi-retired. The number of active clergywomen contrasts sharply when compared to the number of female adherents. The data states that 56 percent of the adherents of the Fellowship are women, and over 1 million of the 2.8 million people who identify themselves as members of the Assemblies were non-white (Asian, African-American, Latino, native American, or of mixed heritage). The complexion and gender ratios are changing within the church because they are changing within the country. Women represent 50.7 percent of all people living in the United States.3 By 2042, white Americans will be the minority, and by 2023, the majority of school-aged children will be children of color.4 These census statistics, combined with the internal data collected by the Fellowship and other denominations, should signal the need for significant change within Protestant church leadership. Women of color should be encouraged to answer the call to full-time ministry. The church must prepare for racial/ethnic clergywomen in an intentional manner. Within the Assemblies of God, several affinity groups based on a variety of ethnic distinctions exist for people of color. Additionally, the Network for Women in Ministry provides data, encouragement, and literature for women pursuing the call of Christ. While the 2008 Conversations speakers deliberately represented a plenary view of women in ministry, the lack of diversity among the conference attendees was rather striking. It would be interesting to interview women of color who attended Conversations 2008 and other conferences for racial/ethnic affinity groups and review the qualitative responses of the participants to understand how each environment ministers to their needs. Local districts should promote these affinity groups to clergy aspirants as a method of finding affirmation and building collegial relationship with other ministers who share an aspect of their duality. Without these relationships, racial/ethnic clergywomen may become isolated in an unhealthy manner and, subsequently, leave the field in pursuit of more comfortable surroundings. I Make Much of My Ministry—but I Could Use Some Help! Senior leadership must explore what institutional support systems are necessary for cross-cultural and female appointments. Typically, academic literature explores three topics: (1) assisting male leadership in cross-cultural appointments, (2) helping women in cross-gender appointments, or (3) supporting women of color as they navigate gender politics within their intra-ethnic congregations. As the national ethnic demographics shift toward a browner society and women begin to enter seminaries in increasing numbers, the leadership of predominately-white ecclesiastical institutions must begin to address the needs of racial/ethnic clergywomen from a dual identity perspective and prepare institutions for this new group of leaders. A Washington Post article about clergy of color leading predominately-white congregations highlighted pastors in Maryland and Virginia.5 The overwhelming response of the male pastors, one African-American and one Asian, indicated that because of globalization and doing God’s will, parishioners are becoming more responsive to their leadership. Conversely, while the Asian woman echoed the men’s comments, she accepts this charge as a missionary for the Lord to the white community and readily acknowledges that her congregants embraced her leadership more slowly than she had anticipated. The African-American female pastor expressed frustration at being the only person of color her parishioners know and stated that although she recognized the purpose of her work, she was simply tired of the arduous task of being the bridge-builder. Fortunately, the African-American woman and the Asian woman belong to a denomination that actively supports racial/ethnic clergywomen. In the United Methodist Church, HiRho Park led the charge for women of color clergy and serves as the Director of Continuing Formation for Ministry. As director, she helps disseminate a study of racial/ethnic clergywomen within the United Methodist Church as a means of helping the church understand the relationship between race, gender, and faith for clergywomen.6 The study examines demographic information and thematic issues such as age, length of time in placement, marital status, salary in comparison to male clergy, and their ability to ascend the denominational ladder. The findings demonstrate that married clergywomen experience less isolation than their single peers and, therefore, enjoy greater overall satisfaction. However, unlike their single counterparts, married female clergy experienced greater tension and critique regarding the dual commitment to ministry and family. When being interviewed for credentialing, married clergywomen were asked to rank their priorities between the ministry and their family—a question many clergywomen did not believe was being asked of their male counterparts. Both single and married clergywomen express dissatisfaction with their pay but remain uncertain whether the pay discrepancy was due to gender or race. The clergywomen relayed several heartbreaking examples of gender and race bias that would make any Christian weep at the thought of such repulsive and solipsistic attitudes. One Asian woman pastor discussed her shame when the ordination board required her to take accent reduction classes before placing her in a church. Her shame did not originate in the request, but upon the discovery that her Asian-born male seminarian peers were never required to take any type of speech therapy to reduce their accents. Another Latina pastor indicated that her assignments were limited to mission-style church plants or churches with limited resources. From her perspective, only Anglo men were assigned to larger suburban churches with Anglo parishioners. Racial/ethnic clergywomen desire to serve in cross-cultural congregations, despite the challenges, as long as adequate support was present. The United Methodist Church (UMC) supports its racial/ethnic clergywomen through a variety of programs. For instance, the Women of Color Scholars program was designed in response to the lack of women of color teaching in the United Methodist seminaries.7 To date, the scholarship has helped twenty-six women complete their PhDs. In addition, the UMC developed a multi-ethnic affinity group for racial/ethnic clergywomen. That affinity group, in turn, created a mentoring initiative entitled, “The Mary-Elizabeth Mentoring Program,” where a seasoned clergywoman mentors a younger female protégé.8One-on-one mentoring can provide significant guidance needed after accepting the audacious call to ministry. One additional source of assistance was a conference specifically targeting pastors of color who lead predominantly white congregations. Identifying fellow sojourners in the body of Christ can mitigate the feelings of isolation for people in Christian leadership. Although some pastors never experience issues with cross-cultural appointments, the majority of these pastors are men crossing a racial boundary or white female pastors crossing a gender boundary. As For Me and My House—We Will Look for Opportunities Certainly, the AG Fellowship embraces racial/ethnic clergywomen and endeavors to bolster support for these pioneering women through various affinity groups. As referenced earlier, The Network promotes diversity among its ranks of credentialed women. Two women represent the National Black Fellowship at the district level, but no women serve on the executive board. The twenty-first century AG Fellowship is reexamining it roots and learning that the church possesses a rich history of women of color at the helm. Jessica Faye Carter wrote an enlightening article outlining some seminal women of color who served within the Assemblies of God—each with their own story of pioneering in response to the call of God.9 These women faced the twin obstacles of gender and racial/ethnic discrimination, but they persisted in their pursuit of Christ. For example, Pandita Ramabai established a home for widows and translated the Bible into Marathi, the fourth most spoken language in India. Cornelia Jones Robertson pastored a California church for 30 years, being one of the first African-American credential holders in the Assemblies of God. Maria de Fatima W. Gomes became the general superintendent of East Timor, possibly the only woman to have ever served as the head of a national fellowship. Clearly, a phenomenal legacy exists upon which women of the twenty-first century can build. These doorways to leadership expand due to the receptivity of senior leadership. Through the encouragement of Jesse Miranda, the number of Latina ministers has increased.10George Wood has received the same approbation for his role in electing a woman to the Executive Presbytery. The broad-mindedness of the presbytery provides a pattern for tolerance on the district-level clergy. The overarching need to supply racial/ethnic clergywomen will increase as the population of the nation shifts. As the parishioners begin to reflect the demographic shift, church staff should reflect the congregation. In the interim, our predominately-white congregations and leadership structures must prepare themselves to embrace, once again, sisters who represent different cultures, languages, and customs. Let the history of the Pentecostal movement serve as a landmark that points the movement in the direction of Scripture. The Word states that our first allegiance is not to a gender or a race, but to unity in Christ.11Let the church and believers persevere to embrace that truth. *Visit Shannon's website for more about her, and follow her on Twitter @shas This article was originally submitted to Dr. Deborah Gill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an AGTS course, “Biblical Theology of Women in Leadership.” End Notes 1. Alicia Vargas, “The Construction of Latina Christology: Invitation to Dialogue” Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary, Currents in Theology and Mission 34 4 (August 2007): 271. 2. Gilbert H. Caldwell, “Black Folk in White Churches,” The Christian Century, February 12, 1969 3. U.S. Census Bureau: State and County QuickFacts,http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html (accessed Dec. 12, 2009). 4. U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives /population/012496.html (accessed Dec. 12, 2009). 5. Phuong Ny, “Minority Pastors Preach Diversity,” Washington Post, http://www.washingtonpost.com (accessed Dec. 12, 2009). 6. Jung Ha Kim and Rosetta Ross, “The Status of Racial and Ethnic Minority Clergywomen in the United Methodist Church” (Paper, General Board for Higher Education and Ministry. The United Methodist Church, Nashville, TN, 2004). 7. United Methodist Church General Board of Higher Education and Ministry, Women of Color Scholars program, http://www.gbhem.org/site/c.lsKSL3POLvF/b.4862847/k.242C/RacialEthnic_Clergywomens_ Consultation.htm (accessed December 12, 2009). 8. United Methodist Church General Board of Higher Education and Ministry, Clergywomen’s News. http://www.gbhem.org/site/apps/nlnet/content3.aspx?c=lsKSL3POLvF&b=5569805&content_id={FE421700-6784-4C8E-BC67-49DB9AE24CEF}¬oc=1 (accessed December 12, 2009). 9. Jessica Faye Carter, “Women of Color and the Assemblies of God,” Assemblies of God Heritage, vol. 28 (2008): 40. 10. Gaston Espinosa, “Liberated and Empowered: The Uphill History of Hispanic Assemblies of God Women in Ministry, 1915-1950,” Assemblies of God Heritage, vol. 28 (2008): 44. 11. Gal. 3:28, All Scriptures, unless otherwise stated, are from Today’s New International Version. Updated: Friday, June 16, 2006 10:22 AM  What was the catalyst for you writing ColorFull? In early 2016 Mattel and American Girl expanded their doll lines to include more diverse skin tones. Having bought dolls for my 3 daughters growing up, I was very happy about this. But I also felt frustrated that these companies could see the need for more racial representation while Christians remained in colorblind mode. I longed to help parents have conversations that celebrate how God intentionally made our features. I drew from journal entries I had made during a difficult ministry season, and formed this story. What was the most difficult part about the publishing process for you? Learning how to query and persevering after getting closed doors. It was hard to stay motivated after Christian publishers kept responding that there was no market for a book like this. I wanted to yell at them, “Duh, that’s why I wrote it!” I assumed secular publishers would be more open to a diverse book topic; but those doors didn’t open either. For a short time, I also considered self-publishing. Because I wasn’t talking publicly about the book & publishing process, often I was temped to just put it on the shelf. I just kept believing since God gave me this book vision, He would open the right door at the right time. Did you have ideas about what the illustrations should look like and how did those ideas align with the illustrators, Ying-Hwa Hu and Cornelius Van Wright? I so wish I were an artist! But I had saved a collection of diverse picture books from my kid’s younger years. In my first editorial meeting I took a few of my favorites that showed the style I favored & the direction I envisioned for ColorFull. That helped us narrow down illustrators and I ultimately choose Cornelius & Ying-Hwa’s style. I am so pleased at how it turned out! What do you hope readers will gain from this book? I hope children and adults will feel a sense of wonder that God made so many wonderful colors on purpose, especially all our skin colors. And I hope black children will be proud to see characters that look like them. Representation matters and this is a book I would have loved to read to my kids when they were young! What is the main concept of ColorFull? Why be colorblind about our skin colors when we can be ColorFull? Be fully aware and appreciative of all the colors God made! How did you grow spiritually from this writing process? As I forged on from closed doors, I found inspiration for more stories. One book turned into a series, which was advantageous when LifeWay’s door opened for me. I saw God’s faithfulness to me and understood the purpose in the process! The refining opened up a treasure chest of writing to share in due time. What advice would you give to others who hope to publish a book? As you embark on this publishing journey of faith, remember God’s faithfulness in times past. Believe in the purpose for the words you have written. When needed, reach out for help and support. Walk the race marked out for you, and don’t compare yourself to anyone else! Is there anything else you’d like to share about this process, being a writer, being a woman of faith? Months ago I heard a message from Lisa Bevere about how God seeds us with desires and hopes, and dares us to dream. That resonated with me because I know God seeded me with this story, watered it with tears and cultivated something beautiful that will in turn, plant seeds into the hearts of our children. This work is a witness that God can take our pain and use it for His purpose. He’s good like that! When is the book going to be available, and where can people purchase it from? ColorFull releases May 1. Visit dorenawilliamson.com to pre-order, or go to LifeWay.com. Book two, ThoughtFull, Discovering the Unique Gifts in Each of Us, can also be pre-ordered.

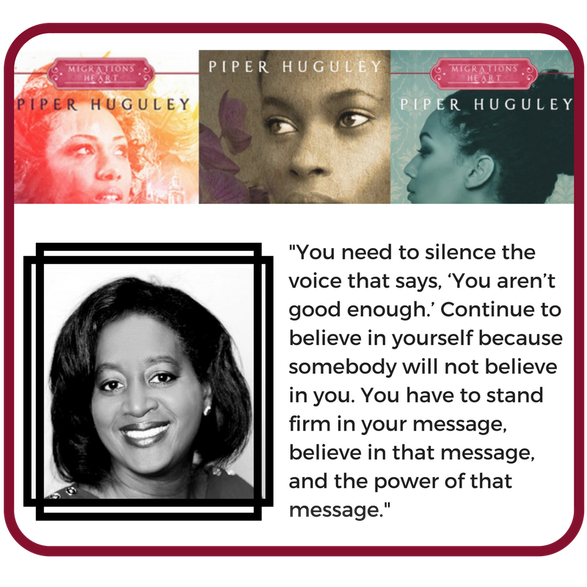

Piper Huguley is an author of historical fiction featuring African American characters. She is an Amazon bestselling author, winner of The Golden Rose Contest in 2013 and Golden Heart finalist in 2013 & 2014. She is a wife, a mom, and a professor.

Piper has been writing on and off for a long time. “Since I was young,” she said. When her son was born, she took a break from writing. A decade later, when he began spending time at football practice, she got back into writing. For Piper, an essay by Langston Hughes, was a catalyst for her writing: Where is the novel or biographical study of Frederick Douglass who defied death to escape from slavery, defied mob-wrath to resist Jim Crow, defied narrowness and convention to side with woman suffrage in a day when women were considered fit only for housewives, defied the racial chauvinism of both his own race and the whites in his second marriage? In other words, a MAN, strong and unafraid, who did not die a suicide, or a mob-victim, or a subject for execution, or a defeated humble beaten-down human being. Douglass lived greatly, triumphed over his times, and left a flaming pattern for the youth of all ages and all countries. But no Negro writes a novel about him. No, we write about caged animals who moan, who cry, who go mad, who are social problems, who have no guts. We have a need for heroes. We have a need for books and plays that will encourage and inspire our youth, set for them examples and patterns of conduct, move and stir them to be forth-right, strong, clear-thinking, and unafraid. Langston Hughes, The Need for Heroes “Most people know about his poetry, but don’t realize he wrote some great prose too,” Piper said. “A lot of what he says is still true. Where is the great biographical of Frederick Douglass, why has it not been released yet?” When it came to publishing, Piper thought she’d publish in the romance genre. “I always thought it would be romance because I thought that’d be an easy place to get published. After a few years of trying … I began to realize on the Christian side how little African American historical fiction there was published especially by African Americans. I thought, ‘Here’s a niche to be filled, let me go ahead and start filling it,’” she said. Piper is a professor at Spelman College near Atlanta Georgia. “I don’t know why it didn’t occur to me sooner to write historical, as my day job as a professor. It wasn’t something I had to do, it was a backdrop of knowledge. Once I decided to go about doing that, I began researching a particular event, which was the Great Migration: the largest intracontinental migration in the U.S.—how black people left the South and went North and West. Knowing that my paternal family was a part of that, I thought to explore that more and develop a series of stories that would explain that,” she said. As she began developing this historically-based series, she realized the call was bigger than she first thought. “It made me come to understand that I owe a debt to the people who came before me and who weren’t as privileged as I am to be able to speak,” she said. “It really struck me that this was something that needs to be done: to speak for those in the past.” Piper said that her research brought her greater insight into her family’s story. She realized that her paternal grandparents’ family migrated in the same fashion as the larger, communal migration pattern that many African Americans followed at the time. “They moved from western Alabama to Atlanta, then a year later to Pittsburgh. It hit me that the place where they lived was just outside the gates of Spelman College where I now teach,” Piper said. She said that her grandmother talked about Spelman college and often wondered what went on behind the gates of the women’s college. While her grandmother was the same age as some of the students, she was not able to attend herself because she was a wife and young mother. Piper said that she sees that her grandmother’s moves allowed her to find out just what went on behind those gates. Piper found publishing her work was an uphill climb. “I just assumed that publishers would throw their doors open, but it didn’t quite work out that way,” she said. “I targeted Historical Romance within the Christian Booksellers Association (CBA)—I was always looking into the romance genre, but after 3 tries, I realized this was not something they wanted to pursue. They started giving excuses, as to why they wouldn’t publish. I realized then that they aren’t going to publish black people and black characters. Even after a certain amount of what I thought was sufficient market research—that was when I understood: OK. That was what the CBA was going to be about,” she said. “At RWA [Romance Writers of American Conference] in 2013 a very important Christian agent told me that my Christian fiction would not be published for 20 years because of the nature of the CBA,” she said. “When I was on the fourth book in the series, the agent told me why my books would not be published in 20 years. She honestly believed she was doing me a favor by letting me know in an upfront way. She failed to realize or care that I had to go through several stages of ‘winning’ in order to get that appointment to talk to that agent in the first place. It was not part of her thought process, that my story had already been vetted by a certain audience. That is how deeply entrenched racism is by the CBA,” Piper said. Around the same time Piper heard this comment, her mother died. “I received a small inheritance that would allow me to self-publish. So my thought was that if I put my story out there, maybe people would see what it is,” she said. “At that point I had two series. So I thought to self-publish one, and then continue submitting the other. That happened simultaneously. I had given up on the CBA and thought maybe the American Booksellers Association (ABA) would take it as historical, which is what happened,” she said. “The irony is that my sweet, inspirational story found acceptance with a publisher who published all kinds of romance stories, but there was no acceptance for it in the CBA. Even the regular publishing industry has their issues with racism, but they can point to their handful of books by African American authors that they publish every year. The CBA has zero. That is the main thing that I really don’t get: this is not Christian behavior,” she said.

Eight years later, Piper said that this is still going on. “I had someone tell me a couple of weeks ago: Maybe there is nobody [African Americans] writing that [fiction with African American characters]. That’s not true. But now you have self-publishing that shows it’s not true. Maybe self-publishing has made them aware and opened their eyes a bit,” she said.

Piper wishes publishers would read the writing on the wall. “Thoroughly backed up by data by Nielson and by the Census: a more diverse United States is coming, in many ways it’s already here. The strategy of excluding POC [people of color] experiences, authors, editors, and marketers from a company is not a long-term answer for survival. In the years since these things have happened, the CBA keeps shrinking,” she said. Piper has some advice for future/current writers. “It’s crucial in any type of publishing career that you take some time building a platform. People think that is something that can be rushed through, but it cannot. It takes a couple of years, minimum of two, to build a platform and to have your message be consistently articulated on that platform. Even if you are traditionally published they are still looking for you to have that,” she said. “You have to put in a certain amount of time and work, and now I’m beginning to see benefits of that. People expect things to happen instantly, and it’s not instant,” she said. “At the same time, while people are building their platform, they can be working on their craft.” Piper said she isn’t sure if self-publishing the one series actually led to the other series being picked up by the ABA. But one thing she is sure about, “You need to silence the voice that says, ‘You aren’t good enough.’ Continue to believe in yourself because somebody will not believe in you. You have to stand firm in your message, believe in that message, and the power of that message,” she said. Find out more about Piper Huguley by visiting her website and her Amazon Author Page. |

Gena's

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed