|

Click the image above to see April's full re-imagined Psalm 23 (with the letter H) at her website https://aprilyamasaki.com

0 Comments

In five months, I had lost the 25 pounds that I intended on losing. Now, six months later, I’ve gained 10 back, and I’m struggling. But I need to write this—now—in the midst of the struggle. Too many of the stories we hear and read and write are those from the mountaintop. But if we are going to trust that God is Lord over our struggles, we have to tell the stories from the ledges, one-quarter up the mountain. We have to tell the stories about re-climbing the same mountain we thought we had conquered years ago. We have to talk about treading the same waters we were once rescued from. This is a story about a zigzagging journey of attempting to lose the weight I’ve struggled with since the birth of my second child nearly three years ago. Last February, I joined a gym. It was a year-long contract. It was after we just rearranged some things in life to free up some extra money. It was an attempt for my husband and I to get back into the shape we were in when we lived in Mexico. I started taking aerobics classes three times a week. I enjoyed it but it soon became clear I couldn’t keep it up because of work schedules and life. So I’d go early in the morning and use the elliptical. I started counting calories after my doctor explained to me what is probably obvious to everyone. I told her I had been going to the gym for a few months, but I wasn’t seeing results. She gave me a math lesson. Calorie intake and calorie burn have a simple relationship with each other. It clicked. I needed to burn more calories and intake less. I moved to the bicycle at the gym because I burned more in the same amount of time. Then I started riding my bike outside. I loved it. I’ve never loved exercising in a building. I’ve jogged outside the majority of my adult life before kids. Things were going great. I was eating healthy, even if I was a bit moody when people ate the things I loved in front of me. I was cycling 3-5 times a week. I had an 8-mile route I took in the early morning before the kids, and the sun, and the city were awake. I loved it. I miss it. Around September we got our foster license. October, we got a call for two girls. We said yes. Suddenly, our routines were shaken. Suddenly, we were exhausted all the time. Suddenly, we were in survival mode. I couldn’t count calories anymore. It took up too much time. I couldn’t think of how I would adapt the family supper to fit my low-intake needs. I could barely think about the next five minutes in front of me. A whirlwind of life came at us fast, and my cycling routine left. I can’t even begin to describe life over the past six months, although my article at Mudroom might give you a glimpse. What I can say is that I have not consistently been cycling since early October, and I haven’t been counting calories. That math formula that sparked my initial change remains constant—and I’m 10 pounds heavier. There’s a moment in rock climbing after you take a big fall. You’re dangling in your harness and you look up at where you were on the mountain and realize you have to reclimb. You have to put your hands in holds you already struggled to grasp and re-find the good nubs for your feet. In that moment you have to ask yourself, ‘Is this worth it?’ I have a lot of work to do in learning to love my body in every shape it finds itself in. I can’t say right now that I do. But I know I need to. I also have to learn that sometimes what we gain in the falling—not in the succeeding—is priceless. The past six months have been the most challenging in MY ENTIRE LIFE. But I would not trade them for a fit body. I would not. I hope that you and I can both learn that God is not just ‘with’ us in the struggles to push us through. He’s with us like— Like dwelling in the struggles Like sleeping on the side of the mountain Like belaying us and encouraging us we can reclimb Like reminding us his love is not earned through successful accomplishments. So when you have to re-climb the same mountain again And when you have to re-tread the same waters again And when you have to re-enter the same dark woods And when you have to return to the places you've been before and never planned on going back ... God is WITH you. On Immigration and the Church

Immigration is certainly not political for Gricel. It’s personal. Gricel is from New York City. “All of my family all the way back as much as I can trace is Puerto Rican. My parents and grandparents migrated to the U.S. wanting a better life. Times were tough and poverty was rampant, and the hurricanes—actually very similar to the situation that is happening right now. The plan was always to go back, but my mother and father never got to. They are both buried in Puerto Rico. That was their desire.” “Immigration is personally tied to my story and so is colorism. It’s extremely personal to me. In our family we have different shades. My mother was blonde, white, and had green eyes. My father was very dark skinned and had course hair. So even though they were both Puerto Rican, there was racism because of their skin color.” This is why she—an ordained pastor in the Evangelical Covenant Church—fights for racial egalitarian justice. On Racial Egalitarian Justice “When I say racial egalitarian, I’m purposely putting race in there because we don’t put those in the same context. What has happened over centuries is that Western Christianity is very patriarchal, very white; and when feminism came in there was a stigma that it was a white movement. It was for white women. All of the marches were organized with white women, by white women, for white women. So Latinas often felt marginalized once again, but now by the feminist movement. ‘Mujerista’ or ‘Latina’ theology … African Americans use ‘womanist’ or liberation theology because they could never identify with feminism … they were not at the same economic level as white Americans, or at the same education level like white America. Even though many of us women of color have overcome in areas of education in the 21st century, there is still inequality with the pay, the positions, the authority, and the power. What should have been something for all women became more of an exclusive movement for the ‘right’ women. In this case the ‘right’ woman was the white woman. And it’s bled into every other area,” she said. “There’s the importance of reframing our narrative and an urgency to do it sooner than later. We need to create spaces where we can have these types of conversations. These are the conversations that I’m longing for,” she said. “Egalitarianism … I didn’t know what that meant in an immigrant church. I knew about equality, I knew about feminism. I knew I wanted my relationships to be equal. I knew that, but I didn’t have the hundred-dollar word ‘egalitarian.’ “When I went to research the term, it felt to me—as a Latina—to be exclusive of my story because it didn’t talk about culture. And you cannot authentically reach people of color about egalitarianism without talking about culture,” she said. “We easily target the things that are irrelevant in Western America and therefore we miss the reality of the authentic story. We don’t take time to listen attentively to the story. The important thing is that stories need to be told, and they should be told by the person who has lived the story. I don’t want you to eliminate my voice in my story,” she said. “The narrative of culture has been absent in egalitarian spaces. They have not done their homework and not seen how important it is to integrate the language of culture and ethnicity in the movement of egalitarianism. Silence is consent, no matter how you slice it. When you don’t talk about it, stereotypes grow in power. Self awareness is so important,” she said. On Language and Dialogue Gricel has ideas on how the church can combat this. “The first thing we have to really learn is that language is powerful. Words are powerful. Words can be inclusive, and words can be exclusive. So when we do things with women and equal rights, we have to be careful that our words are not creating more of a gap in the existing marginalization of women of color,” Gricel said. “Because we don’t see things like you. We don’t have the same experience, and so it becomes a chess game so to speak. We always feel like women of color are always going to get checkmate because we go into these arenas from a deficit from the beginning.” She said that the church needs to be aware that their words, including the wording they use on materials, the platforms, and the visuals which so often exclude the people who look differently than the dominant culture. Conferences often become an experience of pain. “What should be an experience of celebration becomes an experience of pain,” she said. “The [visuals of conferences] tell us another story. We have a lot of work to do. When you go to these conferences especially as a person of color it’s just a harsh reality that much is still the same.” “We can’t continue to talk about the dialogue: ‘Oh everything is great and there is no racism,’” she said. “That in itself brings pain; and racism brings marginalization and seclusion and isolation. It devalues us as human beings. The reality is people of color often aren’t represented; we don’t see us up there. It’s perpetuating a culture of silence because we choose not to talk about it. We’ve never really had this conversation and continued it to its conclusion. We start it, then we zip it, and then we go ‘OK’ and walk on. There’s not a completeness to our conversations on racism. There’s not a complete circle where you go deeper and deeper. We always stay on the outer perimeter of racism, and we always stay on the outer perimeter of egalitarianism. Even when we do have these conversations, they are primarily white and academia theorizing about people when many of them have not been in the trenches and haven’t been on the mission field. People who speak from head knowledge,” she said. On Listening “We need to listen,” Gricel said. “Because we aren’t listening, we are just screaming or talking over each other. We need to stop the incendiary language. We need to have dialogues, conversations, and if it’s painful for you to hear my story, it’s OK. That’s part of the process because my story includes pain, so don’t stop listening because you are uncomfortable with my pain. If you would just move past your discomfort you might learn something about empathy and compassion and mercy and justice … if you just stop thinking about yourself and listen to the stories of others. It’s not about me when I’m listening to someone’s story, it’s about that person. As I listen to that story, I learn from the story. And we aren’t listening to the story. It’s like we are interrupting between the story. When people say things like, ‘If America is so bad why don’t you just go back from where you came from,’—those types of things shut down conversations,” she said. “The biggest accomplishment would be to stop thinking about ourselves when someone else is telling their story.” “For all of us in justice and missions and on the front lines and in the trenches, we really need to probe language and pay attention to how we tell the stories. Because the mission field is right here. I learn by listening to the stories of those around me. As I listen to their stories, I respect them. Listening is respecting. Listening to someone from another culture, engaging with them, and entering into their pain is a sign of respect and honor. We have lost the importance of honoring. We have lost our ability to honor someone who is different from us,” she said. “God, in his plan, made us to be a mosaic of different stories, of different colors, of different perspectives and vantage points,” she said. “In order for us to do missions in the 21st century—missions is now in our back yard—we do missions by listening, by engaging, by honoring and respecting the stories people share.” On Conferences and Church “In everything that we do, a writing conference, women’s conference, men’s conference, pastors’ conference or missions conference, we have to think in color. Everything from the beginning to the end of the planning stages has to be done with color in mind because if not when a person of color comes into the conference they are going to see white. Sterile,” she said. “Those types of atmospheres were never designed for us, they are not for us to camp in, they aren’t meant to comfort us. They aren’t nurturing places. We have made the church that way.” “If you have made your church a hospital, not a lot of people want to come in. I don’t know of anyone who really enjoys being in a hospital, but people respond favorably to places where they receive proper care. Churches and any Christian conference needs to be a healing place, a place of comfort, of safety—another issue for people of color, many do not feel safe in Western Christianity. This translates into the mission field. Jesus said go into all the world, learn about who they are, what’s their experiences. Paul knew about Corinth and the Ephesians. He learned about their cultures and their idols so that he could speak to that. He was coming against the things that were culturally erroneous there. ‘Let me tell you about the unknown God.’ He went into that world and he related to them.” “We have taken culture out, and culture is one of the most important tools to reach people with the gospel. Food is part of culture, music is part of culture, the arts. I know many creative people who are just artistic, extremely gifted, and when I talk to them about God, I first talk to them about their paintings and I can see that the gift comes from God. As I look at what they are painting, I can tell they have painted from pain, or joy, or a difficulty, and I ask them to tell me their story. That’s the way that I can come in. People will open their doors to you if you respect and honor them, when you love them unconditionally, and when you don’t have a hidden agenda,” she said. Advice for a Young Immigrant Christian Woman “Stop trying to be someone else. Be yourself,” she said. “People in the 21st century are tired of the plastic, of people talking about vulnerability, but not practicing it. That is key to women today because we are promoting perfectionism, and perfectionism is counterproductive. The only perfect one is God,” she said. “The stories of people are not pretty, but yet the church says just tell us the pretty stories. Do you see the oxymoron there? The church tells women to tell the pretty stories, because when you tell us the ugly stories you make us feel uncomfortable,” she said. “But you don’t have any way or any right to rewrite my history so that you can be comfortable.” “Crying is not pretty. We need to let people cry. And no, it’s not going to be pretty, but it’ll be healing, and it’ll be restoring. We’re teaching our young women that you have to be strong and fierce all the time. And I believe in strong and fierce, I am strong & fierce, but not all the time. There are times I need a shoulder … I need to be able to release the suffering and the pain and the things that I can’t change,” she said. “I have three women that have stage 4 cancer, it’s not pretty. I don’t have an answer for them. All I can do is walk with them and hear their story.” “Crying is not pretty, life is not pretty, ministry is not pretty, and as a woman pastor it infuriates me when people like Piper say ‘Go home and shut your mouth.’ Who are they to pretend to know about my story and my calling? Do you really think that I would pick this? I have better things that I would have loved to do: paid me more money, I’d be in a bigger house, nicer clothes, get me some Jimmy Choo shoes—get out of here. What women would choose to be pastors? This is the hardest most difficult thing I have done in my entire life. There are times I wake up and I don’t want to do this. ‘God I am really mad at you that you chose this.’ People are nasty and ugly,” she said. She said that she was told at a conference that she would be allowed to speak but she was not allowed to step up to the pulpit and speak from there. She fought against it. “I’m not speaking from down here. Those days are over,” she said. “It’s hard. But when a 15-year-old Latina is in the audience because her mother came and brought her, and she comes up to me and says, ‘I have been praying because I want to preach the gospel and I didn’t see any woman that looks like me doing it, and today I saw you.’ It’s not about me, it’s about God using me,” Gricel said. “We need the visuals. It saddens me when I go to these conferences when its monochromatic because of all those women who are asking themselves, ‘Can I do that? Can I preach the gospel? Can I go to seminary? Can I lay my hands on someone? Can I pray in a public setting? Can I write a book? And they see someone who looks like them, that talks like them, and they say ‘Yes, God that’s my confirmation.’ For those young girls out there, and those seminarians that are thinking of quitting seminary. … God is listening and yes, it is hard, and sometimes they wonder if they can make it another week. So for all those POC let’s show them visuals. That’s what we are here for. That’s what we are here for,” she said. Follow Gricel on twitter @pastorGricel Be here, be whole, show up with all of your bright, un-matching, non-casserole colors and a good side of Korean freckles, take up that space at the table, grab your spoon. Be fearfully & unapologetically you.

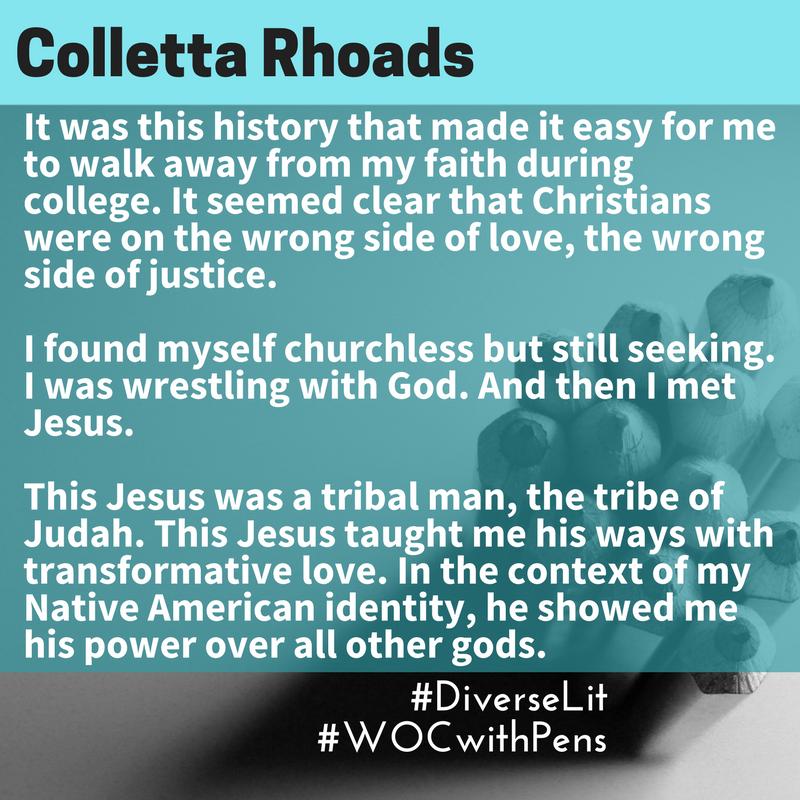

--Tasha Burgoyne https://tashajun.com/2018/03/14/when-being-mixed-makes-you-an-interruption/  “My passion is really John 17:20-23 where Jesus prays prior to going to the cross, that we become one like the father and son are one,” said Bryan Benz, conference manager for the International Wholistic Missions Conference. “And it’s one of those things where I’ve never talked to a fellow believer who disagreed with that, but it isn’t followed very well. Our tendency is that we go out and get something started rather than looking to see who else God has called in that same area and look to join them.” This is why he believes in the conference. “Relationships formed lead to collaboration, and we can accomplish so much more if we are doing it together.” The conference is in its sixth year and has seen some ups and downs. This is Bryan’s third year as the conference manager. With his background in business, he sees how God has prepared him for the job. “Part of the goal for me individually has been to grow the conference in creating income for the Global CHE network: to develop a sustainable business model for them,” he said. Global CHE (Community Health Evangelism) Network is a nonprofit organization that equips churches and organizations across the globe for Christ-centered community development. Bryan also serves as the Operations Facilitator for Global CHE Network. Bryan said he’s trying to refocus the conference on the core values. “Last year in my desire to grow the conference I got away from the focus on the core values. We had 21 tracks and 181 workshops.” This year, there less of both, and all of the speakers and seminar leaders are asked to review the core values: Integration and Wholism, Local Ownership, Participatory Learning, Reproducible and Transferable Strategies, Servant Leadership, and Sustainable Development. “Wholistic ministry is what we are, but we aren’t saying that other ways are wrong, but this is our focus and we want to bring together these core values. We believe that we can work together and learn from one another on how to do that. How we each interpret and act out those core values are going to be different, and that’s OK,” he said. “I think we can continue to learn from others, and my hope is that we influence each other to be better and more effective in the things we are doing.” “I could have easily had another 20 or 30 workshops, I had to tell that many people no. It’s interesting to me. We don’t pay, and if you aren’t willing to stay for the entire conference, you have to pay,” he said. “That goes back to the philosophy is that the value of you as a speaker is for you to be here for the entire conference is so that people can build networks. It also speaks to the idea that we all have to be learners. That’s such a unique philosophy in doing, especially short-term missions, well is that it’s not all about the go word and not all about all this knowledge we have, but to go as a learner,” he said. “It is paramount. Foundationally that’s where we are going with the conference, that you are coming as a learner not as an expert. The whole willingness to collaborate requires such a willingness to humble yourself and to not think you have all the answers,” he said. “If we are going to work together, I’m not going to be able to do everything exactly how I think it should be. I think that’s a big thing. It’s a challenge for all of us,” he said. “So trying to create those environments to boost opportunities to learn and to work together,” he said. “We’re much more likely to work with others if we have a relationship with them. If we understand their heart than we are much more willing, but that’s a process.” “One of the things we did this year along those lines in the conference is that our very first workshop time is Kingdom Connections: our vision is to have 12 separate rooms and as people register they will be assigned a room and during the 75 minutes there will be a facilitator to network and build relationships. We want to do that in the first workshop time to let people get to know one another. On the second day, we’re dividing people in to 12 areas of the world where they are working or feel led to work,” he said. Local Ownership One of the conference’s core values is Local Ownership. I asked Bryan why this is so important. “People are more engaged take better care of things that they own,” he said. “Whether we want to think about renting a house or a car to owning those things. It’s just a different level of how we are engaged in taking care of them. Additionally, I think so much of the world—the developing world in particular—is so fatalistic, there’s a lack of control: of belief that they have any impact. If you go to the places in Liberia: 1 in 5 children were dying prior to age 5. So, for moms with five kids, they feel out of control as to whether or not one of the children will die. But if there is hope that there is something the mother can do and she owns that, then it changes the mindset.” He said that it is important for locals to believe in themselves, “that they don’t have to wait for people outside their community to help solve their problems. That local initiative changes the mindset, it creates an attitude of volunteerism, and all those things lead to sustainability.” “Our tendency as Americans is: ‘I’m going to give you your house, but I’m not going to let you paint it a color I don’t like.’ When the funding is coming from outside there is usually strings tied to it. It’s part of us as people thinking we know best,” Bryan said. “There are those times when realistically you might know what’s best but if you give people ownership, you have to let them determine what’s best themselves.” Sustainability Another core value of the conference is Sustainability. “Sustainability is one of the new buzz words,” Bryan said. “So many of the missions organizations are using the word ‘sustainable’ now. What I see is that as you have discussions, very few of them are using sustainable in a way I would. Resources and money are still coming from outside the community, and at some point that money is going to dry up. Sustainable to me is that the human resources, time resources, and monetary resources are coming from within the community and controlled by the community,” he said. “There is time where things from outside need to be brought in, but going back to the ownership principle, there should be very little outside resources and they cannot come in frequently. The down side of that is that it’s slow: but that’s where you have to start. I was in Uganda evaluating a nonprofit … and all the locals were looking to be adopted by churches in the U.S. They were giving us a list of all of their needs. In each place I said, ‘Well what do you have? What are your resources?’ Trying to change the mindset to the idea that there already exists resources within one’s community. Whether labor or other resources.” “Development takes times,” Bryan said. “It’s much easier to give a man a fish than to teach him how to manage the lake. It’s a much longer process and it’s harder to see results. From what we’ve seen from a funding standpoint, as churches in ministries move into this idea of development it’s harder to show donors results. It’s much easier for me to point out how many bottles of water I gave out or how many backpacks I gave out. But true development: how do you show the progress? It’s a different thing. On STM’s it’s much easier to show I built this house or I painted this house, than to say I built relationships and I empowered others. Those are some of the challenges,” he said. Hindrances for the American Church “In my limited six years of serving at Global CHE, the American Church is much aware that things need to change and that things aren’t working the way they’ve been done. I think it’s a big ship that needs to be turned. My sense is that there is much more of an awareness that it needs to be turned, but there’s a lack of awareness on how. I run into more church leaders that are saying, ‘Yes, it’s not working; but what do we do and how do we do it?’ Earlier it was much more of a why, now it’s much more of a how, so I’m encouraged by that. The focus is in our churches is so much on the goer and what it does for that person as opposed to the receiver. I think it requires training and more effort to change the mindset that the focus should not be all about the goer,” he said. “More people are asking the question, ‘What are we doing when we go?’ It’s still a challenge. The other part of it is, ‘What are we doing when we come home?’” Bryan asked. He said that most people think their short-term trip “has made a lasting impact on their lives but it hasn’t made an impact here in the U.S. I don’t know any church that’s doing a really good job with short-term missions participants coming home. They do a debriefing, but I don’t see them being plugged into discipleship … I’d like to get something started.” “The biggest hindrance for the American Church is time,” he said, “why it’s not being done. The time that it takes to do that. There’s all this prep and training,” he said. Bryan said he’s struggled to make a pathway to facilitate some of these conversations and trainings with church youth. “I’ve offered to go and facilitate, I thought it’d be easier to start with the high school kids. I think these principles would resonate with younger people phenomenally, and I think it’s such a part of what the younger people need. It would impact the number of young people leaving the church because it’s not relevant to them. We’ve created such a performance-minded culture with our youth, totally lacking local ownership, so they become customers of the church not owners of the church,” Bryan said. “I think we need to take baby steps.” Additionally, he said that most ministries are not wholistic. “It’s a whole other challenge. To consider the person’s physical needs and typically most missionaries are all about their spiritual needs. I think we need to start where people are, as opposed to having a predetermined method of how we share the gospel,” he said. Bryan’s Story Bryan has been with Global CHE for six years. He spent 25 years owning and operating gas stations in Tucson. “My businesses failed, and in that process I was searching and questioning if God was in control, asking ‘Why God is this happening?’ Basically through 2011, I ended up making arrangements to sell my business and my last day was Jan 28, 2012. On January 30, I was in Phoenix in what we call a TOT, a training of trainings for CHE. The person leading it is now my boss. Everyone involved in CHE was self-supported missionaries,” he said. “The idea of raising support was overwhelming to me. But the first week of February and next few months God convinced me this is what he wanted me to do. It took a couple of weeks for me to get my courage up to say something to my wife,” he said. Bryan’s wife is a school psychologist working in the public schools. “She supported my decision,” he said. “We are living in the same house we’ve lived in for 16 years … I still struggle with the idea that I’m a missionary—I put quotations around it. We use that word called; it’s part of our separation between the sacred and secular. When I was in the gas station business, I was just as much in ministry as I am now. It’s been a journey, and a struggle because it was a big change. You are going in one direction, I was where I could support missionaries and lead my local church and teaching Sunday School … I thought I was in the right place, but God brought me to a different place,” he said. Click the image above to see Colletta's full post at her website collettarhoads.com

|

Gena's

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed