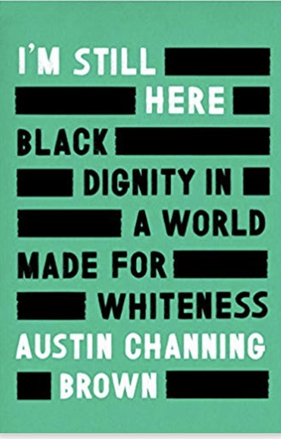

My friend Dee had been working at our predominantly white church for a few years when we became friends. We often talked about getting together but life got in the way for both of us. Then life brought us naturally together. Our boys ended up at the same school, and our families entered into a beautifully deep relationship none of us was expecting. Some days, my husband would pick up her son from school. He’d hang out at our house until she could come pick him up after work. She and I would often sit in my living room chatting about life and church and God and being working moms. These were sacred moments, and we had conversations that revealed the racist undertones of White American Evangelicalism that I knew were there, but I didn’t know know were there. Dee’s knowledge was intimate, her experience deep. As I recently listened to Austin Channing Brown’s book, I’m Still Here, I thought a lot about my conversations with Dee. “White Supremacy is a tradition that must be named in a religion that must be renounced. When this work has not been done, those who live in whiteness become oppressive whether intentional or not.” — Austin Channing Brown While Dee was still working at the church, my husband, Andrew, and I decided to leave. That decision was confirmed after a conversation with the pastor. There were several reasons, but the months leading up to the 2016 election cemented that decision. The amount of rhetoric around how Trump would lead us toward a more Christian politic in our nation made me want to flip tables. It seemed every white Christian around me had excused his immoral behavior because he was quote unquote conservative and would put conservative judges in the courts. His openly racist, misogynistic, and anti-immigrant talk was clearly unchristian to me (which led me to write the article The Abortions of White American Evangelicals that distanced me even more from the spiritual community I had been a part of for a good portion of my adult life). Yet so many of my nonwhite Christians friends saw Trump differently, they saw his immoral behavior and called it out. Andrew and I knew we were at a turning point in our faith walk. We could not continue to attend this church. We had the privilege to walk away. I was questioning our church’s leadership as much as Dee was. And, although I was planning on teaching a course the following semester with a program within the church, when I left, they took my book out of the bookstore and I was not allowed to teach the course. Still, the act of resistance was easier for me and my family—the church wasn’t a source of economic income. Dee and I would have two-hour-long conversations twice a week during that time. When Dee left our house, I’d often meditate on them: how much she’d spur me to deeper faith, the way she’d talk about the Spirit, and how social justice didn’t seem to be an add-on to her faith but rather part of its DNA. Our connection was strong, and we were able to be honest with each other in ways I’ve never been with anyone else. I wondered why my friends in positions of church leadership weren’t listening to her. Her voice was so prophetic, yet she was so often silenced. But why? Now, years later, I realize I’ve still be wondering the same thing. Brown shed light on my unanswered question: “This is why white American churches remain so far from experiencing anything resembling reconciliation. The white Church considers power its birthright rather than its curse. And so, rather than seeking reconciliation, they stage moments of racial harmony that don't challenge the status quo. They organize worship services where the choirs of two racially different churches sing together, where a pastor of a different race preaches a couple of times a year, where they celebrate MLK but don't acknowledge current racial injustices. Acts like these can create beautiful moments of harmony and goodwill, but since they don't change the underlying power structure at the organization, it would be misleading to call them acts of reconciliation. Even worse, when they're not paired with greater change, diversity efforts can have the opposite of their intended effect. They keep the church feeling good, innocent, maybe even progressive, all the while preserving the roots of injustice.” (Italics mine) Power is a greedy thing. And sadly, its expansive ruthlessness is often cloaked in “Doing God’s will” rhetoric. But God showed us a very different example of true power in the life of Christ. God’s equation for power is more like: humility equals power. And honestly, that equation sucks. It goes against all of our earthly values, all of our American values. All of our American Dreams. It’s not easy to accept Jesus for all of who He is. The full Christ is offensively countercultural. “One of the most meaningful passages of Scripture for me is found in the New Testament, where Jesus leads a one-man protest inside the Temple walls. Jesus shouts at the corrupt Temple officials, overturns furniture, sets animals free, blocks the doorways with his body, and carries a weapon—a whip—through the place. Jesus throws folks out the building, and in so doing creates space for the most marginalized to come in: the poor, the wounded, the children. I imagine the next day’s newspapers called Jesus’s anger destructive. But I think those without power would’ve said that his anger led to freedom—the freedom of belonging, the freedom of healing, and the freedom of participating as full members in God’s house.” One of the saddest things about the racism of White Evangelicalism is that the Christ who is so sincerely proclaimed from the pulpit is not fully seen, expressed, or taught. I firmly believe that the robustness of the true Gospel of the Kingdom of God cannot be seen only from one perspective. Yet, it is most often the powerful in society—in ethnicity, in gender, in able-bodies, in economic status—that tell us who Jesus is. Yet they skip over the one-man protest Jesus and tell us (as I was often told growing up) that Jesus is the only one who is allowed to be angry because he’s the only one righteous enough to have just anger. We so often talk about how we need to include the voices on the margins but silence those same voices even when they are already sitting at the table, when they are asking questions with answers that might reveal our greed for power, when they seem angry and we don’t want to ask why they are protesting against the status quo. When they kneel when we think they should stand, and stand when we think they should kneel. We silence Dee and Austin and so many others who have a prophetic perspective of Christ that we white Evangelicals desperately need. And it is to our collective detriment. We want their faces in our marketing pictures, maybe even their names on our payroll, but we don’t want their ideas, their initiatives, their pushback, their balance, their accountability, their prophecy. Because power is our birthright not our curse. Dee no longer works for the church, and she’s flourishing in her new role. We no longer live near each other, but those long conversations remain deep and close to my heart, a constant reminder of the oppression of the white Church, and at the same time, a reminder of what deep spiritual community should be: iron sharpening iron, spurring each other on to greater works of faith. “And even though the Church I love has been the oppressor as often as it has been the champion of the oppressed, I can’t let go of my belief in Church—in a universal body of belonging, in a community that reaches toward love in a world so often filled with hate. I continue to be drawn toward the collective participation of seeking good, even when that means critiquing the institution I love for its commitment to whiteness.” — Austin Channing Brown. *author notes* Everything in Purple is Austin Channing Brown's words from I'm Still Here which you can purchase on Amazon. Dee gave me permission to tell this portion of her story.

0 Comments

"No matter how hard you try to shake him, the god of scarcity is a sticky deity." — Alia Joy, Glorious Weakness. I struggle with how much I feed the god of scarcity when I greedily hoard my time. What do you hoard? What areas of your life is the god of scarcity an idol? And who is the God of Abundance? Can we trust him with everything? "Son, life is about sharing. Don't give what you have left over, rather share what you have now." — María Romero as quoted in Separated by the Border (out Oct. 29) |

Gena's

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed