|

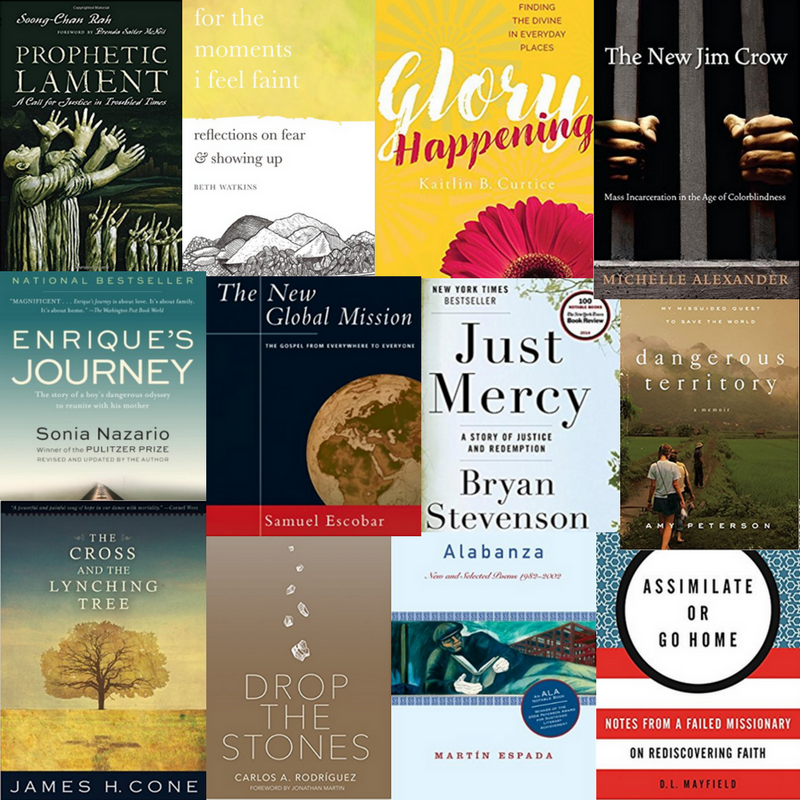

I have decided I won't be reading any new books in 2018 by white men, not because I don't like white men, but because I want to intentionally make space for other nondominant voices. I will continue to read The Myth of Equality with our small group.

Indeed there are so many incredibly Spirit-filled white men who have helped shape my theology and I wanted to give them a shoutout: Walter Bruggemann, Nicholas Wolterstorff, Bryant Myers, Craig Greenfield, Tim Keller, Russell Moore, Shane Claiborne, Lesslie Newbigin, Paul Borthwick, Peter Greer, Andy Crouch, Randy Alcorn, among many others. Many of these men will continue to influence me as I read snippets of their work throughout the year. Tell me, who has profoundly influenced your theology?

1 Comment

A Smoldering Wick is currently self-published through Amazon, after having been published by a publisher that went out of business. Here’s five things I’ve learned along the way.

1. Self-publishing won’t make you a bestseller, but if you have solid content, it will make you a seller. Social media and the internet in general has made all of us more aware of less-known artists. Gone are the days where you have to be in the right place at the right time to become even marginally known for your creativity. I’m not convinced there are more artists out there now, we just know about more artists. This is good and bad. Good in that you, as an artist, have a chance to showcase your work to more than just your close friends and family. Bad in that it feels like you have to shout even louder or be super exceptional to make it ‘big’ (whatever that means). If you are a writer and want to write a book, but maybe don’t have a giant following, self-publishing may be the best option. In some cases, it may be the only option as most traditional publishers won’t take a risk on someone who doesn’t already have a following. (More on that later). 2. Self-publishing requires, nay, demands that you do some self-promotion. If you decide to self-publish, you are going to have to deal with the need to self promote. This doesn’t have to be [too] scary. Without a publisher providing a marketer, you must do your own marketing. This means being active on social media, creating a ‘brand’ identity for yourself and having your own website. (Use tools like website hosts, social media schedulers, and Canva for graphics). This also means you have to get creative and try to get your content out in other mediums such as podcasts and publishing articles that draw people to your book on sites that bring in traffic. This will then increase your following, which simply put, increases the amount of people who interact with your published content. This is why choosing a—one—social media avenue that you can really create a community around is important as an artist if you want to attract a traditional publisher eventually OR if you simply want to have a community of people to engage with on issues you care about. This may not be your goal. Figure out your long-term goals and move forward accordingly. I’d be lying if I said I don’t eventually want to write more books. I started my monthly #JustMissions Twitter chat to promote my book, but also to create a community of people with whom I can interact with about the topic of missions that is so near and dear to my heart. I absolutely love the people I have been able to interact with because of this twitter chat, and have been able to promote others and their work through it, which has been enriching because sometimes its easy to get caught up in the me-me-me of self-promoting and that usually drags me down really low. 3. Self-publishing, unless you are rich, means that you won’t be able to promote your book at conferences with potential readers. This is probably one of my biggest frustrations as a self-published author. Most of my potential readers are at justice-minded or missions-minded conferences, and I can’t get my book on a table there unless I am willing to dish out $1,000+ because the book tables are reserved for the publishers that partner with the conference. Unfortunately, conferences are simply going to have to be a place to network, not a place to sell. 4. Self-publishing requires you to find a good editor and a good cover designer on your own, and, therefore, still costs money and time. OK maybe require isn’t the best word there. It’s not a prerequisite, and most self-publishing companies have options for these services. But the beautiful thing about self-publishing is that you are in control. This means that you CAN work with a graphic designer you like, and you can work with an editor who knows you. So you can go with the services Lulu, Bookbaby, or Smashwords offers or you can find your own services and then go with a self-publishing company that does its pricing a la carte (some of those aforementioned do a la carte). All of these options come with a price (between $500 and $1,500) depending on what services you'll be using from them. In today’s world, I’d highly suggest making sure there is an e-book version of your book, especially if the content is universal or has a global interest. The nice thing about Amazon is that you get 70% of your royalties and you keep the rights to your book, so if Zondervan comes along and sees your book on Amazon that is actually self-published, they can buy the rights directly from you and Amazon won't take a cut. Amazon is also print on demand so they don’t have to shell out money printing up your book that may just sit on a shelf. Then there are other self-publishers who basically are under an umbrella of a traditional publisher but will charge you for their services and will have much more control over what you produce. However, these companies, like Westbow Press, do have some perks. When you pay them, depending on what package you purchase, you'll get both soft copies and e-book exposure on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other big-name websites for e-books. They also promise that their parent companies, like Thomas Nelson and Zondervan, will see your stuff before they see other things because there is a connection there and then your second book maybe will get published by them. I'm not 100% convinced this is true, though it may have been for several authors. They'll do your cover art (if you think that's a perk), and they give you access to their editing services (although the details of that I am not sure). 5. Self-publishing isn’t the only route. There are two routes to traditional publishing: through an agent, OR if a publisher accepts unsolicited manuscripts. Agents can be hard to find, and from what I've read online, it sounds like if you don't know someone who knows someone, the only other way to get an agent is to go to a writing conference and network. I also tried finding an agent in college (yes I wrote a book in college) and it turned out I paid money to them and got no results. However, it's possible to submit your manuscript to online agents I'm sure, I just don't know how trustworthy they'd be. (Feel free to comment below if you know of some trustworthy ones!) The great thing about traditional publishing, is that while you might not have as much control as you'd like, the publisher does a lot of the networking and some of the marketing work (but certainly not all, and I’m hearing its less and less these days) and they have a vested interest in making your book succeed. I was told by one of my graduate professors who has published two books traditionally that her first book made neither the publisher nor her any money, and she advised me to be wary of any company promising to make me rich. I have found some Christian publishers that accept unsolicited manuscripts, some desire the whole book to be sent in, while others only ask for a chapter or two. Most of them want a CV, a book summary and a few other things from you. Whereas it would be kind of nice to know whether or not a publisher will invest in you before you get too far along in the process, it seems like you have to have a good chunk of the book written before they even want to look at you. I imagine there are more, but here is a list of Christian publishers I've found that accepted unsolicited manuscripts at the time of researching. Still, look at different publisher sites and check out if they take unsolicited. Some always take them, others only take them in intervals and under certain categories. Chosen books bakerpublishinggroup.com/chose/contact/submitting-a-proposal New Leaf Publishing nlpg.com/submissions Orbis Books orbisbooks.com/submission-guidelines.html  When a talented writer gets a piece of the pie, today I rejoice. Especially if I had a hand in pushing that pie toward them. But today is today. Yesterday is not, tomorrow is not. The psychology behind trying to be a published writer wears me out often, and when I look at it through the lens of scarcity, I see why. Whether it’s my economic wealth or my lexical fame, scarcity growls like a lion seeking to devour me. Four years ago, my husband and I moved back to North Carolina after living as missionaries in northern Mexico. The American Dream—though we denounced it over and over with our words—was in our hearts and in our minds. We thought we’d finally get to grab a piece of the economic pie that is so massive in our own country, after living for four years off about $1,000 a month. Rather than eating that pie, it was thrown in our face. We struggled over and over again to make ends meet. We were on unemployment, Medicaid, and our children were on WIC. We were grateful for government help, but resented it at the same time. We were grateful for familial help, but resented it at the same time. After three years, we finally had stable jobs, stable income, and we could start paying back the many debts we owed. For those three years, we were in survival mode: always dreaming of a better life, often mad at the dream itself. But what we didn’t realize was that on the other side of survival mode is hoarding mode. And the inbetween of those two modes is as up and down emotionally as survival mode was. One moment we are deeply grateful that we are no longer in survival mode. The next moment we are content; the very next we are fearful that we will fall right back into survival mode. So not only do we hoard to pay for tomorrow, we hoard to repay for yesterday. Our past and our future are filled with nightmares of scarcity. And so it goes with writing fame. One moment I am deeply grateful for all the publishers who have given me a piece of the pie. The next moment I am content. The very next, I am fearful that I will fall right back into a time and place where no one knows my name, and no one cares about the words I toil over. Nightmares of scarcity are never calmed by gaining more. In an economy where production is an idol, nightmares of scarcity are never scarce. In Sabbath as Resistance, Walter Bruggemann says, “That violent restlessness makes neighborliness nearly impossible. … The narrative is a rendering of recurring social relationships legitimated by anti-neighborly gods who give warrant, in the interest of commodity, to redefine neighbors as slaves, threats, rivals, and competitors.” And indeed, whether in survival mode or in hoarding mode, it is easy to see my neighbors as threats. But rest comes in the form of neighborliness. So I challenge myself and all my other writer colleagues to actively reject the idea that there is only so much room at the publisher’s table. To reject that there are only a certain amount of eyes that will read our words. Even as I write this, there is a voice in my head that says: ‘but it’s true, there is only a certain amount of space at the table.’ Yes, we now live in an era where we see a myriad of artists around us—and as an artist that can be simultaneously encouraging and discouraging. And yes, it’s harder to get a book published in some ways because you have to have the big platform we all love and hate simultaneously. But there are tangible disruptors among all of this: new grassroots blogs, new magazines, new networks. Still, we need intangible disruption as well. As we keep trying to make our way in, may we be the internal disruptors:

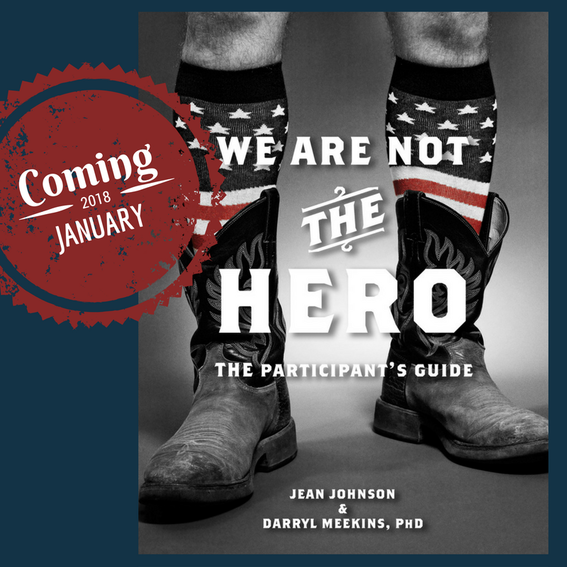

Jean Johnson is the director of Five Stones Global and the author of We Are Not the Hero. She was a missionary in Cambodia for 16 years. Prior to her time in Cambodia, she moved into a one-bedroom apartment upper duplex with a Cambodian family of eight in Minneapolis. She works to promote and implement ways of cultivating indigenous movements for Christ that both sustain and multiply over the long term. Living intentionally in the United States among Cambodian immigrants was something that sprang from her bible school training. “When I decided to go the missions route and study Cross Cultural Communications, there was a professor/director of missions that who had a vision for something different than the mainstream,” she said. At the college, he designed a training program that captured the heart and the enthusiasm of the students by sending them out on a two-year cross-cultural assignment as soon as they graduated. “Part of our training was to live fairly incarnationally among those we served. This meant using local transportation, having a mild income that required living by faith, learning the heart language through immersion, and living with the people.” As soon as Jean graduated, she activated this identification style of mission among first-generation Cambodian refugees in Minneapolis. Other students went overseas, but Cambodia was not an accessible country, so she decided to start at the homefront. Due to this training, she embraced an incarnational mode of mission as her norm. “With the denomination I was with, you study, you gradate, then you spend two years as a traditional pastor in America before you could go on the field. The organization provided the missionaries with a nice budget. [This professor] wanted to do some things different than the typical sending route. He wanted to capture the heart of the students.” She said that oftentimes, by the time students completed the two years serving as traditional pastors, they would no longer want to be involved in missions. “I don’t think he wanted to get us out of the system, he wanted us to stay in the systems the denomination provided. He therefore created a program that was two years with training stemming from the incarnational mentality.” So, Jean had a choice to enter the incarnational route or the pastoral route. She was only allowed to raise a certain amount of money for her incarnational living. Language was to be learned by immersion, and transportation was limited to what the locals used. Not long after Jean moved from the bible school classroom to the Cambodian one-room apartment, the incarnational part of her program was cut off. “The system didn’t like the program, and then stopped it while I was there. I had a choice: just keep going—at that point I was licensed with my denomination—so I became a home missionary. I didn’t change anything; I just kept on that path,” she said. “It wasn’t revolutionary to me because I was a fairly new Christian at the time and thus. I didn’t have as much traditional baggage. I bought into [incarnational living] rather quickly,” she said. But her ease into that life was based on a stepping stone from her adolescence. “In high school, at the time the Cambodian, Hmong, and /Vietnamese refugees were coming into my comfort zone and social spaces, I felt called to make friends with them. It was God-driven but I didn’t know at the time. That identity was in me, having a whole chunk of people from another culture land in my social space overnight was good for me. I went to their homes, ate their noodles, I did with them what I did with my Anglo friends. I didn’t have an idea of what missions was. It was a gut experience encountering people who were different from me, and I learned to lean into it.” Jean said that once she began living with the Cambodian family, sleeping in the hallway, she couldn’t back-pedal because her organization had changed its mind. Jean firmly believes in local sustainability within missions. When asked why that is so important, she rests firm on the Bible. “If you were to peel back which reason is most rooted in me, it is my take on the Bible. You can’t point to an example in the New Testament church Bible where there is a chronic ethnocentric going back to one group visiting and one-way giving to the same group over and over. There was communal sharing and accountability was organically built in accountability. . The discipline in all of that happening was internally. Jesus’ model for the disciples —they were mobile was rooted in mobility—if you don’t do stuff sustainability in a sustainable manner, you can’t be mobile. I don’t see Jesus creating stopping and setting up non-sustainable structures and projects and then staying on to maintain them. Take Paul, he didn’t subsidize the churches that he planted. I can’t find any examples of that,” she said. Jean said that when she speaks of sustainability, she’s speaking of it being locally sustainable, without outside funding. “I feel like in the biblical framework, Jesus set up a ‘church’ that should naturally sustain itself. When we set it up as we do, we add things to it that aren’t sustainable. I believe that the cultural insiders are responsible for reaching their own Jerusalem,” she said. “I go to Cambodia and lead them to Christ. They now have their Jerusalem. I don’t believe it’s my responsibility to keep reaching their Jerusalem. It’s their responsibility to reach their own Jerusalem. For sustainability, whatever I do … I think if I’m Paul, I want Timothy to do it without me. I didn’t always do it that way. I had to intentionally work that that way. I didn’t know you could do church without a building. I wish someone would have told me that. I wish my assignment was: Go make disciples, but you’re not allowed to create a church building with church services. In the USA, we are accustomed to starting churches to make disciples, not the other way around. When you are in sending organizations, The mission senders and sending organizations they count the tangibles:, they want church buildings, they want bible school buildings, projects, and numbers. There are a lot of things with the traditional missions model, that I didn’t feel comfortable with.” Those normal missions models didn’t seem to have space for what she was doing. “My desires and/or attempts at incarnational methods models got swallowed up by these systems,” she said. Jean and I met at this year’s Vulnerable Mission conference in Pittsburgh. One of her talks was entitled, “An Unhealthy Self-Image Equals an Unhealthy Community Image.” She said, “A healthy self-image of a church is a church that owns their biblical responsibility of what a church should be—not my definition of what it should be. They should both own that and then mobilize local resources for that. What I mean by ‘that’ is Those are the main functions of being the body of Christ. Non-healthy self-images include statements like, ‘We are too poor; we need a sponsor.’ ‘We’re not good enough, smart enough.’ ‘We want to love our neighbors, but we can’t do it until we get a medical team.’ ‘Why should we support our pastor?’” she said. “Anything that makes a community look outside of itself to be the body of Christ is unhealthy. The belief is that, ‘I can’t unless I have dot dot dot.’” Jean desires that missionaries and mission agencies would recognize that there is a dependency issue, and acknowledge the biblical church model as a way to address dependency. “If we could reimagine the church to begin with, if we could dismantle the framework that says the church in Acts is a primitive church—let’s get back to that church.” *** Coming soon is the Participant's Guide to We Are Not the Hero |

Gena's

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed