|

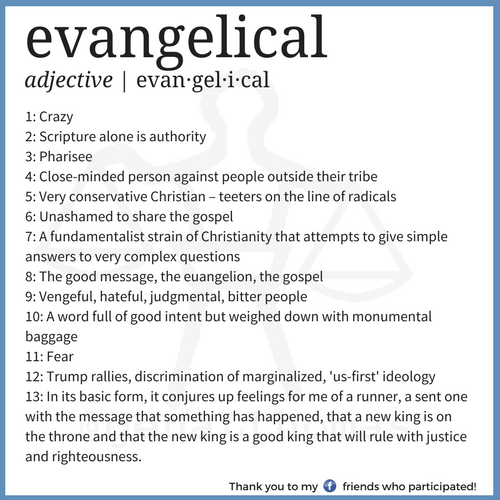

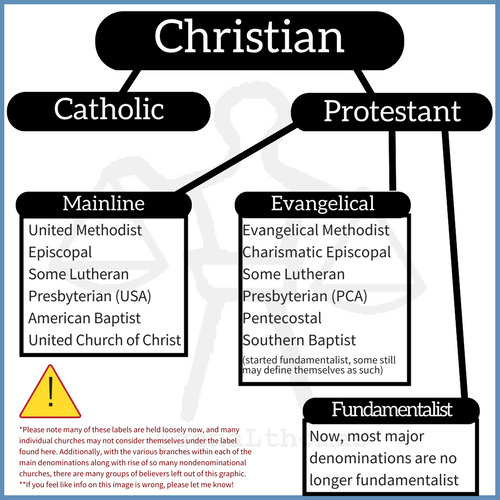

You must get along with each other. You must learn to be considerate of one another, cultivating a life in common. …You’re all picking sides, going around saying, “I’m on Paul’s side,” or “I’m for Apollos,” or “Peter is my man,” or “I’m in the Messiah group.” I ask you, “Has the Messiah been chopped up in little pieces so we can each have a relic all our own? Was Paul crucified for you? -1 Corinthians 1:10, 12-13 (MSG) “It’s easy to make a case that our society is increasingly treating the neighbor has a threat and not a neighbor and increasingly distorting God for the worship of idols. I don’t think that’s a progressive or liberal judgment, I think that’s an evangelical judgment, and I believe that’s the conversation we ought to be having.” Walter Brueggemann, in his interview The Bible for Normal People podcast. The word “evangelical” has been abuzz for the past two years. Everyone has their own definition of what it means. Unconsciously growing up evangelical, I never knew the word existed. Protestant, I knew, because I’m half Italian and it was a big deal when my mom quit going to Catholic mass and started going to a Protestant service. My great uncle, Neil, was a Catholic priest; his twin sister, Grace, is a Catholic nun. Grace and I had many conversations as I was coming of age. She challenged my faith a lot, in a good way. She lives in Rochester, New York, and is always fighting on behalf of the poor. It’s relatively normal for us to hear she’s been thrown in jail. The lives of Neil and Grace always offered a powerful counter balance to the negatives I heard about Catholics from Protestants. I wonder if I offered the same to them. When I lived in Mexico, the word evangelical was typical. It replaced Protestant in my mind, as “evangelicos” was often used as an identifier of our sect of Christianity. But I had no idea where it came from. The many months leading up to the U.S. presidential election, I heard the word again and again, not sure what it meant to each person using it. After three years of life back in the U.S. preceded by more than four years living in Mexico, Andrew and I left our home church. It was an excruciatingly difficult decision. We didn’t want to be consumer Christians, we didn’t want to be unfaithful to the Bride of Christ. We struggled to differentiate between reverse culture shock and actual issues within the church. We often felt we were fighting against the spirit of the American Church more than just the spirit of our own local branch of it. All of this has led us to ask some deep, difficult questions. It’s also led us to ask some simple ones: what is church? What should it look like? What reasons are valid for leaving a church? What reasons are simply superficial? Where do we belong? What tribe are we? What other tribes exist? Clearly, the word is dichotomized. Full of good AND bad. Most of the people who responded to this are Christians. So the question for those of us commonly known as evangelicals is will we choose to keep the label or not? You can read about how I immediately struggled with throwing off this label in my Missio Alliance article: The Abortions of White American Evangelicals. We can also decide to forget labels altogether – although the temptation sounds good, but coming from someone who has yet to call a local church home and has no idea what denomination that future church will be, I have to agree with my friend Kaitlin Curtice: “We exist beyond our labels, but our labels guide the spaces we inhabit and the arguments we make.”

But just like money, love, power, and any other possession, the gospel calls us to hold things with an open hand – and that includes our labels. Evangelicalism is where it is right now because those in the movement held too tightly to the label, and forgot about why the label is there in the first place. Anytime we are close-fisted, that possession begins possessing us, and we lay our lives down for an idol. If evangelical means one who carries the good news, we evangelicals need to reawaken to what that good news is. The good news tells us to love God and love neighbor. It says that the Imago Dei is imprinted on every human being (every neighbor): this means that ISIS members, Joseph Kony, a serial-killer, a rapist, along with an innocent 6-year-old, a new-born baby, an upstanding citizen, a straight-A college-bound virgin high school senior, a woman who had an abortion and marches for the rights for others to have the same choice, a single dad struggling to make ends meet working 3 jobs to stay afloat, and yes, even Donald Trump himself all have the imprint of God within them. This means that the good news is for everyone. Everyone. It means that no human being is too far gone to be transformed by the blood of Jesus Christ. But that good news also tells us that we are wrong when we think the imprint of God means we are God, and we are wrong when we think the imprint of God no longer exists within ourselves or within someone else. The moment we think that is the moment we say God cannot redeem that person. When the human being believes himself to be omniscient, the Omnipotent becomes human. When we say Donald Trump no longer has a soul, we are actually saying God no longer has muscles. That’s not so bad to say if we are feeling righteous, but when we are in the spiritual dumps because of some bad choice we made, we need a God with muscles. We need a gospel that pulls us out. Our Messiah has not been chopped up into little pieces. He’s still alive. He’s still fighting for the poor, the marginalized, fighting for shalom, fighting against the bad yet fighting for the bad guy, fighting against sin. His muscles are as big as they’ve ever been, regardless of the labels we give each other. He didn’t create labels, he created multi-faceted human beings. “We exist beyond our labels,” Kaitlin said. Without a doubt, we must be on the mission of bringing the good news into our spaces. Without a doubt we must be about loving God and loving neighbor – and doing our best to live grounded in the good news that those two are inseparable. As for me, I’m still an evangelical – though I know that label has some major issues. Every label does. It’s OK if you decide it’s not a label you want to wear anymore. I get that. Labels may come and go, but salvation and redemption come neither through labels nor by dropping them. At their best, they bring belonging and sharpening. At their worst, they become idols. For the Christian, whether Catholic or Protestant or any subgroup thereof, identity must come not from labels but from a relationship with the God who became man, dwelled among us and offers us an upside-down shalom-minded kingdom that says no one is too far gone from redemption and that redemption is directly linked to showing love for ‘other’. As Kaitlin says, "I wait and watch as people learn to be human to each other, to step over dividing lines to remember that we belong to each other."

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Gena's

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed